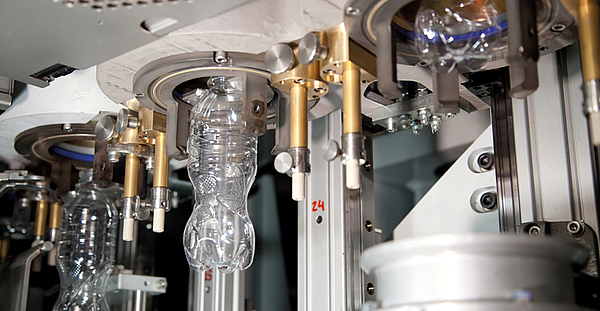

Photo credit: Sidel

A Retrospective Analysis of the PET-Bottle

How does Sidel view the issue around PET?

"SIDEL": The name is an acronym of the French “Societé Industrielle Des Emballages Légers”, the “Industrial Company of Light Packaging”. Monica Gimre, CEO, Sidel and Vincent Le Guen, Vice President Packaging look back on the company history going back nearly 170 years.

Where are the roots of the company and when, how and why did their entry into PET technology take place?

Le Guen: Sidel has a history going back nearly 170 years. In 1850, Simonazzi Workshops was founded in Parma, Italy, by Pompeo Simonazzi, who saw an opportunity to offer mechanical equipment to local farmers, later extending his capabilities to filling and bottling of beverages. Roughly one hundred years later, in 1965, Sidel was founded in Le Havre, France, by Georges Lesieur, having evolved from Lesieur Group’s Lightweight Packages division. The name is an acronym of the French “Societé Industrielle Des Emballages Légers”, the “Industrial Company of Light Packaging”. In 2005, the two organisations merged when Simonazzi joined the Tetra Laval Group, creating a company capable of providing complete liquid-packaging solutions for the beverage industry. Sidel also has a history with Gebo and Cermex. Cermex was founded in Corcelles lès Cîteaux in 1974, and quickly became a leader in case-packing and palletizing. In 1996, the company joined the Sidel Group. Gebo was founded in Reichstett, France, in 1964 by Gustave Schoen, a specialist in engineering and conveying. They were acquired by the Sidel Group in 1997. In 2003, the Sidel Group, including Gebo and Cermex, joined the Tetra Laval Group. As pioneers in the packaging industry, Sidel strongly believed in the potential of PET material already back in the 1970s. When the first PET blowmoulder was sold to a customer in the UK in 1979 to produce carbonated soft drinks, the machine was running at 360 bottles per hour per mould. The industry knows, but it is always interesting to remember the technological advancements in this field: today, the two stage stretch blow moulding machine is able to run at 2,700 bottles per hour per mould, so 7.5 times faster.

How would the company development possibly have gone without the introduction of PET technology?

Le Guen: This is, of course, a highly speculative question. We can really only say that PVC was at the end of its cycle. We saw low performances, e.g. PVC was not suitable for carbonated drinks; it is not recyclable and even harmful to the environment. This was why we started to investigate business opportunities into other packaging materials, i.e. PET, which was already in the market but not for food-related applications.

As one of the pioneers of the PET packaging industry, Sidel believed in the potential of PET back in the 1970s. How did you describe and quantify the potential of PET at that time?

Le Guen: Back in the 1970s, we couldn’t ignore that the growth of Carbonated Soft Drinks (CSD) was not properly addressed by glass and other plastics. In the following decade, we launched various innovative blowing technologies in close cooperation with customers in the United States, the most dynamic market in terms of PET adoption at that moment in time.

How could you describe the dominance of glass and can in the years 1960-75 and what shaped the competition between these packaging materials? What were weaknesses of these packaging materials? Which critical points did these types of packaging offer compared to PET - and are these points still valid today?

Le Guen: We have to remember that back in the 60s and 70s, there were simply no packaging options for large size containers: glass was simply not viable due to the high risks for explosion associated with carbonation and familysize bottles. Therefore, PET took up speed quickly as an alternative, based on its safety and its resistance to breakages. That said, glass has some other weaknesses, such as its heavy weight and the central manufacturing. Cans, on the other hand, are much lighter than glass and are fully recyclable but they had the disadvantages of needing a lot of energy during production and not being re-sealable. Originally, PET entered the carbonated soft drinks markets because of its resistance to pressure and its 20-fold weight reduction compared to glass, thus becoming an enabler for market expansion around this beverage segment, successfully winning in terms of safety, cost affordability, convenience and transport challenges. Talking still beverages, PVC was giving the same lightweight advantage compared to glass, but was taken over by PET thanks to PET’s 100% recyclability potential, with the main outlet being fibre application and other non-food applications. The above points still remain completely valid today.

When did PET take on a leading role in the market?

Le Guen: PET started taking on a leading role between the end of the 80s and the early 90s, at the beginning especially in the beverage segment. After the success of PET bottles for all types of drinks, Sidel started engineering PET packaging alternatives for food, home care and personal care products. For example, in 1993, the first PET jars with wide-mouth for food were launched on the market.

A year later, the preferential heating blowing process offered the possibility to produce complex shapes and flat PET containers for home care and personal care industries, as well as for food and condiments, such as mayonnaise and ketchup. But the journey was long from being over: in 1997, we revolutionised the PET bottle production by combining blowing, filling and capping in one single solution with the Combi configuration. Compared with traditional standalone equipment, the integration of the different production phases into a single system eliminates conveying, empty bottles handling, accumulation and storage. The Combi development, therefore, offers a huge advantage in terms of significant bottle lightweighting opportunities and great freedom of shape for each container.

What was the focus of the developments: the needs of consumers or those of the bottling industry? Which of the two was the driving force?

Le Guen: We can say that both had their part to play in positioning PET as the leading packaging material in the beverage industry. On the one hand, the bottlers saw its benefits in terms of safety, lightweighting, transparency, design flexibility and affordability of the raw material. Consumers, on the other hand, particularly appreciated its minimal weight and the much greater convenience that PET had to offer.

What was the PVC bottle like? Was it technical/technological or environmental issues or environmental activists who made life difficult for PVC as a packaging material?

Le Guen: There were a number of factors at play that made PVC not ideal as a packaging material. For example, the PVC bottle was exposed to cracks because of its high fragility; it was not transparent, difficult to lightweight, and PVC, as mentioned, was not suitable for CSDs. Last but not least, its end of life was quite challenging, as the burning of PVC leads to the generation of toxic fumes.

What were the technological challenges at the beginning with PET as a new material?

Le Guen: The main technical challenges at the beginning were two-fold: for one, the bottle stability was an issue. Before the invention of the Petaloid base, the bottle base was typically hemispherical and was not quite stable, when standing on a table. To overcome this, we went for the so-called “base-cup”, mentioned above, which brought its own complexities in terms of implementation. The second big challenge was the increasing blowing speed, which was needed to support mass market requirements. As indicated before, the first SBO blower, in 1979, was running at 360 bottles per hour per mould (bphm). Today, the industry standard is to 2,700 bphm. All of that while maximizing lightweighting opportunities and flexibility, i.e. through fully automatic or very easy and fast changeovers. This naturally required a great focus on innovation, both in terms of packaging and engineering.

Which significant technological and mechanical engineering developments has the PET bottle or machines experienced to this day? Please provide a short of timeline.

Le Guen: In the 80s, we started developing blowing technologies tailored to specific industry segments. In 1986, Sidel released the Heat-Resistant (HR) blower – an industry first – to produce PET bottles for juices, isotonics and teas, withstanding high filling temperatures, between 85°C to 92°C.

''The main technical challenges at the beginning were two-fold: for one, the bottle stability was an issue.'' - Vincent Le Guen

Just two years later, the first industrial Sidel blower to produce refillable PET bottles, able to resist numerous washing and refilling cycles, was introduced to the market. In 1994, our preferential heating solutions were launched, to answer the needs of players active in the food, home and personal care segments. But the journey was long from being over: in 1997, Sidel revolutionised the production of PET bottles by proposing the Combi blow/ fill/cap solution. It was this impactful change that allowed us to take the first step in the RightWeight™ packaging approach via different technologies and packaging solutions through the decades. In 1999, then, Sidel Actis™ was the first coating solution to improve PET barrier properties to gas and oxygen, in order to increase the shelf life of carbonated soft drinks and beer while simultaneously decreasing the bottle weight. In 2007, Sidel celebrated another milestone and designed what was by then the world’s lightest 500 ml PET bottle for water – with the Sidel No Bottle™ weighing just 9.9 g. The developments in the Liquid Dairy Products (LDP) were not standing still during this time either. In 2009, the first PET bottle for UHT milk filled in aseptic conditions was achieved with Predis™. This unique dry preform sterilisation technology had been launched in 2006 and three years ago has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), another world first. In 2013, we introduced our Sidel MatrixTM system, the modular, extremely scalable platform aimed at efficiently supporting any producer’s individual requirement. Later on, the StarLITE™ CSD base, launched in 2014, was able to increase the overall resistance and stability of PET bottles. Three years later, StarLITE TROPICAL was released and is able to resist very high temperatures and humidity rates, perfect for tropical climates. This innovation ensures better performance of PET bottles for CSD, which are produced and distributed in extreme environmental conditions. Two more innovations I would like to mention are BoostPRIME™, which is a unique PET packaging solution, offering an innovative alternative for hot-filled beverages in PET bottles. Launched in 2018, this solution uses our Base Overstroke System (BOSS) completed with a bottle base inversion after filling and before labelling. And lastly, the world’s lightest bottle for non-pressurised still water (6.5 g of weight), Sidel X-LITE StillTM – the most cost-effective and sustainable packaging available on the market – was introduced to the market in mid-2019.

Which developments originated from the demands of the consumers, which from Sidel’s own ideas?

Le Guen: Heat-resistant blowing and preferential heating developments were clearly driven by customer needs. When it comes to aseptic PET packaging the bottlers required more and more simple and safe solutions and Sidel was able to innovate through the Predis system, our proven dry preform sterilisation technology. The Predis differs from other aseptic bottling technologies because the PET package sterilisation already takes place at the preform rather than during the bottling phase. Thus, the solution marks an important step towards a sustainable production because it does not require any water and uses only minimal amounts of chemicals: all of that while eliminating the constraints related to the bottle shape’s complexity and exploiting PET lightweighting opportunities. The solution is able to handle bottle formats from 200 ml to 3 L with any shape, at speeds up to 60,000 bottles per hour.

What has driven the industry for the past 15-20 years? And what drove it in the beginning of the PET industry?

Le Guen: The main driver of the industry has always been productivity, based on increasing output speeds and packaging lightweighting opportunities. For example, in 1990, a 500 ml bottle for still water weighed 19 g and was produced with 34 bars of blowing pressure. This required 6.3 watt-hours per bottle, with an output speed of 1,000 bottles per hour. 30 years later, with Sidel’s X-LITE Still, the output speed has increased by 170% to 2,700 bottles per hour at only 6.5 g of bottle weight. Additionally, energy needs have decreased by 50%, down to 17 bars of blowing pressure and 2.3 watt-hours/bottle.

What are today's challenges in the packaging market? Which advantages and disadvantages does PET have here?

Gimre: Talking challenges, it would be naive not to recognise that we are living in an era when plastics is perceived as a contributor to pollution and PET bottles can be found in marine litter. The biggest issue today is public perception, which is largely based on misconceptions and driven by emotions. Note that PET represents only 5% of the global plastic production. Despite the fact that PET is the best packaging material in terms of environmental impact, on top of the many other advantages it offers, such as food safety, lightweighting potential, design flexibility, transparency, affordability, we acknowledge that education of the end consumers on the full supply chain and better management of waste are key success factors for a true circular economy of plastics.

How would you describe the market in terms of sustainability in the early days?

Le Guen: The notion of sustainability, or more precisely “sustainable development”, was kicked off between the late 80s and the early 90s; one of the main founding acts being the Brudtland commission report for the United Nations. The environmental toolkit with the ISO 14000 series on environmental management, Life Cycle Analysis tools, etc. developed very fast in that period. We can say that from the early 2000s, sustainability took off in most of the business organisations, becoming a clear customer and consumer focus. From the very beginning, in the food and beverage industry, PET as a packaging material already bore significant advantages versus aluminum cans and glass in terms of sustainability. Glass factories were and still are huge fossil resource consumers. In addition, glass bottle production has to be centralised, therefore generating huge CO2 emissions linked to the transportation of the heavy bottles. Aluminum cans, although they are light, have similar issues when it comes to energy consumption: aluminum production plants have to be close to power plants and can manufacturing is too complex to be implemented in a filling plant, generating the need for transportation, coming along with additional costs and a bigger impact on the environment. The sustainability attributes of PET greatly helped it to develop fast. In other words, the sustainability attributes of PET greatly helped it to develop fast. Besides that, as mentioned, they were a determining factor in the conversion of bottled water from PVC to PET.

When did the subject of PET recycling come up? When was it discussed for food grade?

Le Guen: PET recycling has been developing in parallel with the increasing use of this packaging material as a preferred solution in the beverage industry. In the early 80s, the polyester fiber market was starving for recycled PET and companies such as Wellman jumped into the business of bottle-tofiber recycling. A few years later, in the late 80s, Plastipak founded Cleantech to recycle HDPE as well as PET containers.

''The main technical challenges at the beginning were two-fold: for one, the bottle stability was an issue.'' - Vincent Le Guen

In the non-food sector, Colgate has been using recycled PET for a long time, benefitting from a lower resin cost. Actually, a number of visionaries understood that recycling and protecting the environment was key to packaging. For instance, about 25 years ago, Antoine Riboud, founder and former CEO of Danone, understood that the benefits of single use packaging could only work if a strong cooperation across the value chain was established in parallel to avoid plastic pollution, therefore contributing to the launch of Eco-Emballages (nowadays CITEO) in France. The use of recycled PET into food containers started with multilayer technology and was led in the early days by Continental PET Technologies, a company now owned by Graham Packaging. Recycled PET was integrated as a middle layer of the preform, ensuring a functional barrier. Developments for direct food contact PET recycling started in the US in the early 90s, with the FDA issuing a letter of non-objection around the Supercycle process. In Europe, a common process for food contact approval was established only in 2008, under the guidance of EFSA, allowing a faster development of bottle-to-bottle recycling. Last but not least: chemical recycling was already part of the agenda in the 90s, but the business case wasn’t there.

What significance did PET recycling have and what technical developments did it trigger?

Le Guen: Let’s talk about the challenges ahead. Nowadays, the demand for food grade r-PET is so high that r-PET is sold at higher prices than virgin PET. On the other hand, we need both an acceptable quantity and quality to implement improvements and increase the level of automatisation of the sorting technologies. We expect this to continue in the coming years, but at the cost of efficiency, and eventually resulting in lower profitability. Improved quality of the collected PET material looks as a more sound and sustainable solution. It can be achieved through effective design to recycle and by strengthening collection methods and streams. On the latter set of measures, reverse vending machines via separate streams, deposit schemes, as well as financial incentives, have proven to be the most efficient ones. Chemical recycling is often proposed as an alternative mean to obtain higher quality recycled material. Without digging into the various processes, we could say yes – in principle. However, the quality of the incoming material will impact the efficiency of these recycling processes, too. In essence, quality collection remains key.

Consider the CO2 footprint using the example of a 0.5 L water bottle: How did the PET bottle perform in 1990 and how in 2020? How will this look in 2025? Are there any comparisons with glass and cardboard packaging?

Le Guen: I would like to use a real life example, comparing our X-LITE Still bottle solution – designed for nonpressurised water bottled in PET, a 500 ml format, 6.5 g – with a regular 500 ml PET bottle, weighing about 12g. Electricity saving per bottle equals 4 Wh, translating to a reduction of carbon footprint per bottle comparable to 1.2 g eq. CO2./1/ When comparing glass to PET in terms of their respective production processes, we have to consider both the eco profiles of the materials and the weight of the packaging for the same functional unit. For instance, to produce one kilogram of PET, the energy involved is 69 MJ/kg: this means that for a 0.5 l, 12 g bottle the energy impact will be 828 joules per bottle. On the other hand, to produce one kilogram of glass, the energy needed is at 16.6 MJ/kg, meaning that for 0.5 l, weighing between 200 and 300 g, the energy impact will be ranging from 3,320 joules to 4,980 joules per bottle. For both materials, the rule is: the higher the recycling rate, the lower the carbon footprint. This phenomenon is more significant for PET than for glass. In glass production, whatever the recycling rate, you still need to melt it at 1,600°C and the main, yet slight, improvement is on the yield of the oven. With recycled PET, the many steps starting from extraction of fossil resources to the production of the polymer are avoided, leading to a major reduction of energy use and carbon footprint. In Europe, the typical carbon footprint of virgin PET is 2.15 kg CO2 equivalent/kg. It drops down to 0.45 kg CO2 eq./kg with 100% mechanically recycled PET. Secondly, we can also compare the carbon footprint linked to the whole lifecycle of refillable glass and refillable PET. The following projection considers a 500 ml bottle format, for CSD, in Europe, and is taking into account both today’s collection rates and a hypothetical future with 90% collection rates. Currently, a refillable PET bottle, weighing 48 g, only has 78.4% of the carbon footprint that a one-way 500 ml PET bottle has. In comparison, a refillable glass bottle has a 21.2% ‘worse’ carbon footprint than our one-way 500 ml PET reference bottle. Even in our hypothetical future with a 95% return rate for refillable bottles, 7 years life time of a bottle with 3 trips/ year of 500 km, the refillable glass bottle still performs approximately 17% ‘worse’ than a one-way 500 ml PET bottle today, and much worse than the refillable PET bottle in this hypothetical future./2/ This means that refillable glass is only convenient when the distance between the production plant and the retailer, i.e. the distribution point, is short; otherwise, PET packaging performs much better in terms of the CO2 footprint. We expect the lightweighting of a PET bottle to be determined by consumer acceptance. However, the container will integrate more and more recycled content, from an average of 10%, which is the status quo today in Europe, to a value ranging from 30% (in Europe by 2030) to 50%, depending on the development of collection and recycling capacity. With 30% to 50% recycled content, even if bottle weights would not be reduced, an estimated Green House Gases (GHG) saving, ranging from 6 to 11 g eq. CO2 per bottle, would be possible./3/ As mentioned above, there is typically a gap between public perception on what the best environmental packaging solution is and what the reality is. We are expecting some changes in consumers’ attitude towards packaging. What will happen in the near future will depend on the alternatives that are available on the market, how they are perceived as environmentally friendly, convenient and affordable.

What are the developments to become even more sustainable? How are they communicated to the consumer?

Gimre: Sidel has always been working along the ideas of the circular economy but expectations recently evolved. Originally, one of the main drivers behind the conversion from PVC to PET was the latter’s 100% recyclability potential, with the main outlet being fibre application and other non-food applications. Today, closing the loop via food grade bottleto-bottle mechanical recycling is gaining real traction.In our daily work, we strive to avoid all waste, minimise greenhouse gas emissions, cut water and energy c onsumption, and promote recyclability. Additionally, as part of our End to End approach, we look at packaging and equipment with a 360° perspective. Not only do we need to take into account primary, secondary and tertiary packaging but also their interaction with the equipment in the factory. Moreover, we need to consider the impacts they create upstream and downstream in the value chain. Lastly, by signing the New Plastics Economy Global Commitment, we have undertaken another important step towards a more sustainable future. This worldwide initiative was launched by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation and UN Environment in October 2018 with the goal of addressing the plastic waste and pollution crisis at its source and keeping plastics within the economy. Today, it unites more than 400 organisations on its common vision of a circular economy for plastics. Obviously, all our customers have set aggressive goals around circular economy commitments. Several companies stepped up in 2018: in October, French multinational Danone pledged to produce 100 percent circular packaging by 2025.

''Today, closing the loop via food grade bottle-to-bottle mechanical recycling is gaining real traction.'' - Monica Gimre

Around 86 percent of the company’s packaging is already circular, and half of its water volumes are sold in reusable packaging. /4/ Coca-Cola pledged to collect and recycle 100 percent of its beverage packaging by 2030./5/ Nestlé, the world’s largest food company, made a similar commitment last year, pledging to make all of its packaging recyclable or reusable by 2025./6/ Earlier this year, PepsiCo launched “Recycling with Purpose”, a circular economy model that will promote recycling in Latin America and the Caribbean. One of Recycling with Purpose’s three main components is a consumer incentive approach that helps educate and involve consumers in recycling.

Can patents be an indicator on how the main focus around blow molding machines has shifted?

Le Guen: The PET blow moulding business is a rather young business where we still see a lot of patents registered every year. The latter aspect is a clear indicator of the high innovation component in our industry. When it comes to the blow moulding part of the portfolio, the patents are especially addressing opportunities for equipment optimisation.

Why do certain developments, such as the coating of PET bottles, still struggle with acceptance by customers?

Le Guen: The beverage industry has been traditionally facing very low acceptance rates around recycled bottles, with or without coating, but we can see the consumer perception is changing fast. As a case in point, in a recent success story, Sidel supported StrongPack Ltd., a Nigerian co-packer, in its mission to become the number one, high-quality, non-alcoholic contract packaging company in Africa. As part of this greenfield project, StrongPack installed a total of four complete lines, including a PET line integrating Sidel’s ActisTM coating system. This unique plasma coating solution can extend the shelf life of beverages bottled in PET, while enabling package lightweighting with no compromises on recyclability. It is used mainly in packaging CSDs, beer and oxygen sensitive beverages such as juices, tea or coffee. Helped by the Actis technology and the increased shelf life of the PET bottles, StrongPack is now able to reach additional markets in West Africa that otherwise would not be available to them. In addition – while refreshing their bottles’ designs – the Nigerian co-packer was able to achieve a 25% reduction of the containers’ weight, allowing them to roughly save about three tons of PET resin per day.

What is it like for Sidel as a plastics machinery manufacturer to be part of a carton packaging corporation?

Le Guen: Let me allow a clarification here: Sidel is one of the three industry groups forming the Tetra Laval Group, together with Tetra Pak and DeLaval. Those companies are focused on technologies for the efficient production, packaging and distribution of food. DeLaval is a market leader and trusted partner for thousands of farmers around the planet, providing integrated milking solutions designed to improve dairy farmers’ production, animal welfare and overall quality of life. The company develops, manufactures and markets equipment for milk production and animal husbandry worldwide. Tetra Pak is the world’s leading food processing and packaging solutions company. Working closely with customers across the globe, they provide a broad range of innovative products, technologies and services, helping to make food safe and available, everywhere.

There have been standard and custom developments in the industry, such as preferential heating: Which of these developments have gained a lasting importance for PET technology?

Le Guen: Three developments have been deeply influencing the industry. First, we need to mention the Heat-Resistant (HR) blowing, which allows us to package juice, isotonics and teas in hot-fill PET; secondly, we should note preferential heating with which we control the material distribution for an ideal container shape and wall thickness, and thirdly, the dry preform sterilisation with Predis, which I described above.

What have been the most serious mistakes or shortcomings in the PET packaging industry in general, and at Sidel in particular?

Le Guen: Nowadays, we are significantly strengthening the cooperation with all the actors in the packaging value chain – from FMCG manufacturers, brand owners, NGOs, to OEMs, master batch suppliers and, of course, the end consumers. Only by closely working together can we make a true circular economy of plastics possible.

Do you give PET a chance for the future? Would Sidel start and invest in the PET sector today?

Gimre: At Sidel, we believe that PET is the best answer to the current sustainability challenge, as long as you are properly collecting and recycling it. Looking at primary packaging in general – also beyond beverage – PET is one of the most widely used consumer plastics. The advantages of PET as a packaging material are numerous: it is strong, unbreakable, light, transparent, safe, and above all recyclable. As a lightweight material, PET offers considerable environmental advantages in the form of lower transport costs and reduced fuel emissions. Its unique geometric properties and inherent barrier properties, together with its design flexibility, have enabled producers to use less and less material in the packaging process, while optimising energy use. These processes also help reduce waste and improve sustainability measures. With the world currently consuming more resources than it can hope to carry on producing, the shift in consumer attitudes towards a circular economy is resulting in:

- A reduction of the types of plastics that can be used as packaging materials. PET – as a consequence – is expected to gain market share, because of the properties I just indicated

- It can help rethink secondary and tertiary packaging toward alternative materials or reusable solutions

- It may open up new distribution vessels in addition to our traditional PET, glass, can, and refillable packaging solutions

- In emerging countries without a decent water distribution network, the current packaging solutions will stay crucial, thus contributing to a strengthening of efforts on collection and recycling.

We are welcoming these developments towards higher collection goals, together with the measures suggested for increasing adoption of all recyclable packaging materials. They will have a positive environmental impact, definitively changing the image of packaging and opening opportunities for higher levels of recycled content embedded in future packages.

Let’s imagine that PET is reinvented today. What would a so-called green field approach change? In the value chain and in the industry?

Le Guen: Since the birth of the PET industry, the supply chain was purely concentrating on building massive PET manufacturing capabilities;

''We will continue to design to recycle - which is was, is and remains a top priority for us." - Vincent Le Guen

if done today, we should balance this manufacturing capacity with an appropriate end of life capacity and infrastructures (i.e. to cover collection, sorting, recycling) to be fully neutral in terms of environmental footprint.

The PET bottle - what would be its downfall?

Le Guen: Even though PET is suffering from a negative public perception, based on misconceptions from end consumers and poor collection schemes, we should remember that it is the only plastic that is 100% recyclable bottle-to-bottle and that the usage of r-PET is already a reality today. Our new X-LITE Still packaging solution, for example, is compatible with r-PET, as long as the quality of the r-PET is appropriate. According to the blowing tests we performed under industrial conditions, X-LITE Still can contain between 25% and 50% of r PET, yet ensuring the quality and the performance of the bottle. Additionally, our blowmoulding equipment is technically able to process any concentration of r-PET, provided that it is of good quality. To ensure this, as mentioned earlier, wellorganised recycling streams need to be in place.

What actions are you already taking today and in the future to make your PET packaging visions become a reality?

Le Guen: We will continue to design to recycle – which was, is and remains a top priority for us. For instance, by partnering with Sukano, a global specialist in the development and production of additive and colour master batches and compounds for polyester and specialty resins, we have recently technically proven that making light barrier white opaque PET bottles from recycled material is possible – and can be done at the same throughput. The collaboration demonstrated that light barrier white opaque PET bottles can indeed be up to 100% bottle-to-bottle recycled, going back to the same application or being upcycled and used for new addedvalue outlets. In essence, we saw no measurable difference in processing conditions or blowing output while processing the 100% recycled white PET material from Sukano-designed white master batches, even under the most challenging conditions. This is a good example of how challenges which looked very complex in the near past can be overcome through close collaboration across the industry.

_______________________________________________________________________

/1/ This hypothesis takes into consideration the European situation, where a KWh equals 300 g of CO2 equivalent emissions.

/2/ This one lies at 70.6% of the carbon footprint compared to the reference bottle.

/3/ This hypothesis is based on a PET bottle weighing 12 g.

/4/ https://www.danone.com/impact/planet/packaging-positive-circular-economy.html

The comPETence center provides your organisation with a dynamic, cost effective way to promote your products and services.

magazine

Find our premium articles, interviews, reports and more

in 3 issues in 2025.