The discovery could result in a recycling solution for millions of tonnes of plastic bottles, made of polyethylene terephthalate, or PET, which currently persists for hundreds of years in the environment.

The research was led by teams at the University of Portsmouth and the US Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) and is published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

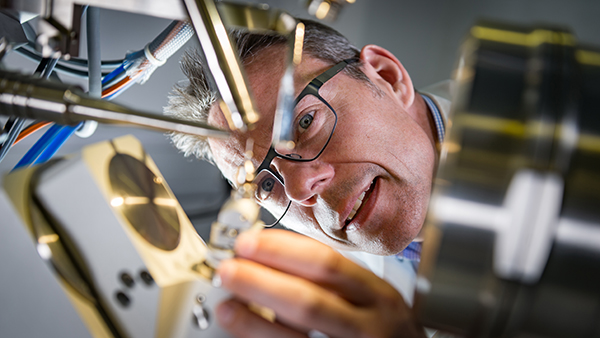

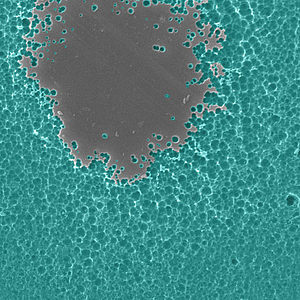

Professor John McGeehan at the University of Portsmouth and Dr Gregg Beckham at NREL solved the crystal structure of PETase—a recently discovered enzyme that digests PET— and used this 3D information to understand how it works. During this study, they inadvertently engineered an enzyme that is even better at degrading the plastic than the one that evolved in nature.

The researchers are now working on improving the enzyme further to allow it to be used industrially to break down plastics in a fraction of the time.

Professor McGeehan, Director of the Institute of Biological and Biomedical Sciences in the School of Biological Sciences at Portsmouth, said: “Few could have predicted that since plastics became popular in the 1960s huge plastic waste patches would be found floating in oceans, or washed up on once pristine beaches all over the world.

“We can all play a significant part in dealing with the plastic problem, but the scientific community who ultimately created these ‘wonder-materials’, must now use all the technology at their disposal to develop real solutions.”