(Photo credit: PETnology)

Interview

Eastman - Accelerating Circularity: Unlocking the Full Potential of Recycled PET with Chemical Recycling

Through advanced recycling technologies, Eastman offers high-quality recycled PET solutions designed to address industry gaps and challenges in achieving circularity. - To achieve true circularity, the industry must move beyond ambition and embrace action. From streamlined material qualification processes and market acceptance of sustainable pricing, to stronger supply chains and supportive regulations—collaboration is key. In this interview, Eastman shares what it will take to scale chemical recycling and build resilient circular economies worldwide.

Eastman has a long-standing legacy as a leading PET supplier and pioneer in material innovation. With decades of expertise, the company is tackling the global plastic waste challenge and developing solutions in line with key regulations such as SUPD, PPWR, and the Circular Economy Act.

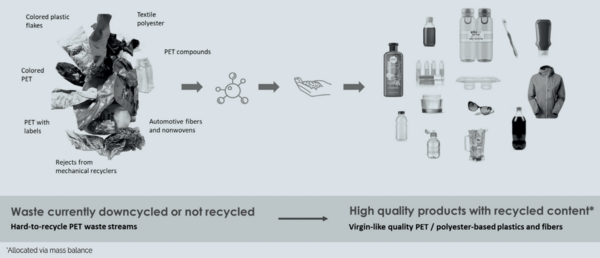

Having pioneered methanolysis technology in the 1970s, Eastman is now scaling this advanced recycling method globally, offering high-quality recycled PET for applications where mechanical recycling alone falls short.

In this interview with Eric Dehouck and Matthias Matthias De Vel we will discuss how Eastman is driving innovation in PET recycling and the role chemical recycling plays in achieving true circularity.

What industries do you currently supply with plastic materials?

Eric: We serve and support a wide range of industries, including cosmetics, eyewear, medical supplies, food and beverages, FMCG and general packaging, such as containers and films. We also operate in the textile / fibers sector.

Matthias: In all these areas, we work with our 2 main technologies platforms: our copolyester and cellulosic ester platforms, both are based on ester chemistry: one is derived from synthetic monomers and the other from biobased cellulosics. While the value chains across these applications are similar, each one has its own nuances.

Sustainability

What role does sustainability play, particularly in relation to polyester and copolyester solutions?

Matthias: Consumer behavior is playing an increasingly important role. Take PET packaging, for example. It’s a pioneer in sustainability and recycling. Over the last five or six years, we’ve worked hard to adapt to the changing demands of the market.

Eric: The growing focus on sustainability has highlighted the value of polyester in the circular economy, especially since ester chemistry lends itself well to recycling. Although this concept has been around for some time, it has not yet been clearly positioned as a value proposition in the market. We are currently implementing this strategy through chemical recycling, a depolymerization process, also known as “molecular recycling“.

Eastman has not been active in the PET packaging market for a long time. What has changed to prompt your re-entry into the market?

Eric: The last five years have been a period of significant growth and development for us. Initially, we focused our copolyesters on more specialized markets, with different dynamics than those of traditional commodity PET packaging. However, we are now reintroducing PET into the packaging sector, through our high-quality, virgin like recycled PET offer.* We recognize that the market is currently challenging due to its high degree of commoditization and intense competition. Nevertheless, we are confident that our molecularly recycled materials provide substantial added value and a unique quality. Driven by regulations, demand for sustainable PET solutions appears to be growing, and we are excited to contribute to this area.

Matthias: Eastman has officially returned to the PET packaging business, this time through a highvalue sustainable PET. We left the market in 2010 and sold our assets. However, the shift toward circular economy models has opened up new opportunities, and we are re-entering the market with clear goals. The feedback has been extremely positive. People in my network and former industry contacts have told me they are excited to see Eastman return. Our name still carries a lot of weight, and we bring valuable contributions to the table.

Past omissions

The technologies for chemical recycling had been available in the 1970s. Why wasn’t it marketed at that time?

Eric: In the 1970s, the focus was on maximizing profitability by recovering valuable materials, such as copper and rare earths. Waste disposal and reuse were not yet issues of concern.

Matthias: Today, what has changed is awareness. The waste crisis is now front and center. When we view these older Eastman chemical recycling technologies from the 1970s through this lens, we see their tremendous potential to address today’s challenges. This shift in mindset, from profit optimization to sustainability, is what distinguishes the past from the present.

Eric: As Matthias mentioned, we have all become much more aware of the waste crisis. This shift in thinking is important. Today, at Eastman, we believe that we have the right technology to tackle a part of this very important challenge. It’s not just about recovering materials anymore; it’s about finding scalable, long-term global solutions. That’s the main difference between then and now. However, for real change to happen in the market, consumers must be able to make conscious choices. This requires knowing about and purchasing products and materials that are more circular, even if they are not the cheapest or most convenient option. For that to happen, however, people need to be informed. They must understand the impact and be willing to make small sacrifices.

______________

''With the rise of circular economy models. The response has been very positive -Eastman is a trusted brand, and people are glad to see us back.'' - Eric Dehouck

______________

What led to this change at Eastman, and how important are sustainability goals for your company today?

Eric: Ultimately, it’s about the vision: the vision of the CEO, the board, and the management team. This vision is clear: Address one of the most pressing challenges of our time by creating a true circular economy. As a manufacturer of plastic materials, we cannot sit back and wait for others to solve this problem. We must ask ourselves: What role can we play? Then, we must commit to it.

For a long time, the motto of material manufacturers was to sit back and wait. Could you please describe the situation that led to this change in thinking?

Eric: Many plastics are indispensable to our modern lives, and there are no viable alternatives, but we must acknowledge that there is a major issue about plastics end-of-life. Today, around 460 million tons of plastic are produced every year, but we estimate that only about 9% of it is actually recycled. And it goes even deeper than that. This 9% usually refers to a single recycling cycle. In reality, much of it is either downcycled or reused only once. It means that after one or two cycles almost nothing remains recyclable. The central challenge is that if we want a circular economy, we need technologies that enable high-yield upcycling. This applies to all materials: PET, copper, silver, etc. Without these technologies, we are merely delaying incineration or landfill, not closing the loop.

Old and new world

Returning to the transition between old and new ways of thinking, where do you currently see the greatest resistance?

Eric: I believe there will be enormous challenges. If I have learned one thing from my work in industry and the markets, it is this: whenever a new paradigm emerges, the old one resists. It’s a survival instinct. So, we are witnessing tectonic forces colliding: the old world – the linear economy - colliding with the new – the circular economy. It’s never a smooth process and each one needs to find its new setting. There will be ups and downs, delays, and setbacks. Ultimately, however, I am confident that circular economy will find its way and will prevail because we have a limited amount of virgin resources on the planet.

What makes you so sure?

Eric: Our technology is unique: we can produce virgin-like quality from waste at a very high yield. Isn’t it a great news? We take PET waste that would normally end up in landfills or incinerators and transform it back into high-quality PET suitable for food and medical applications, with a yield of more than 90%.

But at what cost?

Eric: Yes, the technology is capital-intensive. However, when you break it down, the additional cost of circularity is less than a penny - one penny - per bottle. Therefore, the ultimate question is: as humans, citizens and professionals, are we willing to pay 1 penny more by bottle to create a true circular economy.

Strategies and challenges

What were the strategic reasons for the investments: Market opportunities, regulations, or responsibility?

Eric: Responsibility. We have the technology. What makes our approach to chemical recycling special is that it is truly material-to-material. Pyrolysis, methanolysis, and glycolysis all fall under the broader category of chemical recycling but reflect very different “worldviews.” With our methanolysis technology, we can convert waste into food-grade PET at a high yield. That’s impressive - and that’s why we do it.

Matthias: Of course, regulations are also an important driver. I believe that we need regulations. We must be humble enough to admit that habits do not change without regulatory pressure. Many things that we now consider “normal” have only become so because regulations were introduced 50 years ago. So why not do the same now? We should demand that products are not only recyclable but also made from recycled materials. Otherwise, we’re just kidding ourselves.

Are market opportunities relevant?

Eric: Ultimately, it boils down to one question: Is the circular economy economically viable? In my opinion, the answer is yes, provided that companies can grow and thrive within this framework. If not, economic forces will destroy the circular economy - or any other meaningful transition. We are not doing this out of pure idealism. We are doing it because it is a viable business model, one that happens to solve a major environmental challenge. This is the win-win situation we should strive for. We’re doing it because it makes economic sense. If we want the circular economy to succeed, we must play by the rules of the global free market. To me, the circular economy must be profitable, attractive, and capable of growth. Otherwise, it won’t be a sustainable business model; it’ll just be a way to ease our consciences.

So that’s one of the strategies: making the circular economy a profitable business.

Eric: Exactly. When I speak with politicians or civil servants, I tell them, “Of course we expect a return on investments like this. Just like any other company.” I added, “We shouldn’t be shy about saying that we want to be profitable.” This is what will make this business sustainable and drive further investments. Let’s be honest: If we can’t make it profitable, no one else will. The circular economy can only work if it offers financial value, just like any other economic model. A question could be: what does it take to make a circular economy business financially attractive?

______________

''A circular economy cannot be built with good intentions alone. It must be profitable, scalable, and attractive within market conditions. Otherwise, it will not endure.'' - Eric Dehouck

_____________

What is your business case?

Eric: We have already started worldwide. We are up and running in the U.S., and the technology is working even better than expected with higher yields, improved purification, and better overall efficiency. We are currently supplying customers with chemically recycled PET, and the response has been positive. For us, this is a profitable business.

Matthias: The real challenge now is scalability. In order to expand the business, we need to look at regions such as Europe, North America, and parts of Asia, ideally where the legal framework supports such a development. Without this support, it will be difficult. Recycled materials are often more expensive than virgin ones. To create a truly fair system, we would have to consider the total life cycle costs of new materials. If these costs were reflected in the market price, recycled PET would often be just as affordable as virgin PET or even cheaper.

Eric: The bigger question is: Are we as a society ready to take this step? Are we ready to pay the full environmental cost of a product’s life cycle? If not, then we are not ready for a circular economy

In May at our PETnology conference, Eric, you spoke about a threatened value chain in the chemical industry. What specific developments are you observing?

Eric: Yes, the value chain is indeed at risk. I can predict something: With the raise of energy cost in Europe since 2021 (destruction of Nord Stream II), the German chemical industry has begun to suffer, especially heavy chemical manufacturing. Next will be fine chemicals, followed by the molecular industry, and eventually, the pharmaceutical industry. Ultimately, this will have an inevitable knock-on effect on the basic materials industry. Why? Because the competitive energy supply that powered all of this is no longer available.

At the conference, you also mentioned a massive loss of knowledge in Europe. How do you see that playing out?

Eric: I need to back up a bit here. We are seeing value chains in areas such as mechanical engineering, electronics, and automation begin to falter. When too many jobs - and with them, expertise - disappear, the effects often only become apparent 15 or 20 years later. By then, you have lost not only your customers but also your industrial base and technical know-how. Rebuilding that takes years. Take battery manufacturing, for example. I worked in this field for many years. Projects such as Northvolt in Europe are currently struggling because they can’t compete with cheaper imports from China. This is a real turning point. The question is, what role do we want to play in this value chain? That’s why I’m speaking up. This is not just about one company or one product, it’s about the entire industrial ecosystem. Unequal competitive conditions can destabilize the entire ecosystem.

This is a challenging and critical situation, not only in the recycling sector. The key to success lies in both the overall value chain system and finding the best technical solution. In your view, what constitutes an advanced recycling solution?

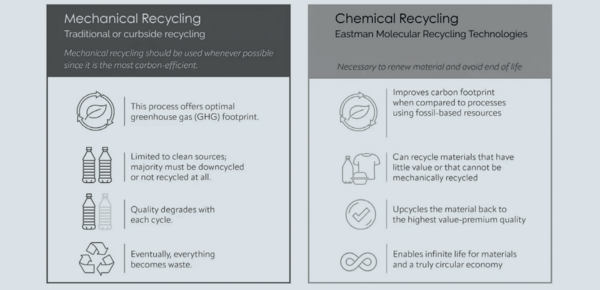

Eric: That’s a good question, and it’s not always easy to answer. Let me start with mechanical recycling. Mechanical recycling is exactly that: mechanical. The material is collected, washed, shredded, stored in silos, and extruded back into granules. In some cases, a cleaning step can be added to improve quality, usually through chemical reactions applied to the granulate.

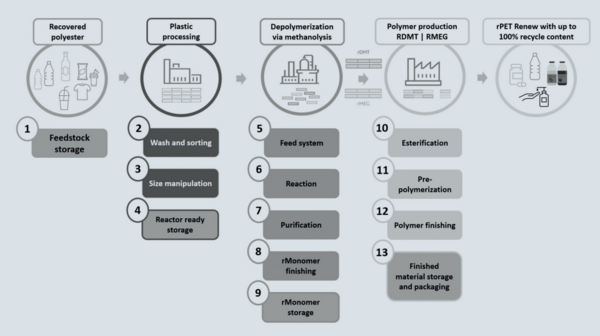

Matthias: What we do with chemical recycling goes further. We take plastic waste and completely break down the polymer chains, right down to the molecular level. Then, we go through around ten cleaning steps before reassembling the molecules into a new, high-quality material. It’s a real molecular reset.

Mechanical and chemical recycling

You mentioned technical, qualitative, and economic limitations. Do you see these limitations in mechanical recycling as well? It seems that you favor chemical recycling.

Eric: Thanks for the question! Let me clarify: We are not competing with mechanical recycling; we are complementing it. Since we announced our entry into chemical recycling, many mechanical recyclers have viewed us as a threat. Some have even said, “You’re going to ruin our industry”. People often try to pit mechanical and chemical recycling against each other. But that’s a false dichotomy. We don’t use the same raw materials, capital model, or business logic. However, we share a common interest in maintaining a robust local recycling infrastructure. Mechanical recyclers typically do two things. First, they take clear PET bottles that have been collected separately and recycle them into new clear bottles. This process works well and should continue to do so. Second, they process colored or opaque bottles and recycle them into granulate used for downcycled applications. This is also a legitimate market. Neither of these is what we do. Why? Simply put, our technology is more capital-intensive than mechanical recycling. Competing in this segment makes no sense for us – it’s not economically viable. That’s why we take a different approach: we take material that mechanical recyclers cannot use, material that would otherwise end up in an incinerator or landfill. This is where we create added value.

Mechanical and chemical recycling are not mutually exclusive. Why is it important for both approaches to coexist?

Eric: As mentioned, we convert waste that mechanical recyclers cannot use back into foodgrade PET. We are not competing with them, on the contrary: I want mechanical recyclers to succeed. Nothing would make me happier than seeing them flourish. Why? Because they are hit hardest and first by unfair imports, especially from Asia. This is already happening; mechanical recyclers are closing down one after the other. That’s bad news. If they fail, it means the market is not ready for a circular economy, at least not a fair one. At the same time, thousands of jobs will be lost. If mechanical recyclers fail, the machinery industry will fail too, right? We’re talking about recycling plants and the machines used for washing and sorting. They won’t survive in Europe. To me, a healthy mechanical recycling industry is a sign of a functioning system. This means that local players are protected, and we can build on that by converting fractions that cannot be mechanically recycled into food-grade materials. Without a strong regional recycling infrastructure, the entire concept of the circular economy collapses. We would end up incinerating our own waste or worse, importing low‑quality recycled pellets from overseas to manufacture products that sometimes couldn’t even be sold in their countries of origin. Turning a good intention to recycle our waste in Europe into this counterproductive outcome is clearly irrational! I believe that future generations, perhaps even anthropologists will look back and ask, “What on earth were they thinking?” And I fear they will be right.

Are mechanical and chemical recycling comparable processes that simply occur differently?

Matthias: The presence of methanolysis in our process indicates a higher degree of purity, which is considered the “pinnacle” of purity. Therefore, the term “chemical recycling” is somewhat misleading because a valid comparison between the mechanical and chemical processes is not possible. This is precisely the point at issue here.

Let’s take a look at the process. Let’s assume we have a PET bottle that contains EVOH or nylon. How does that affect your process?

Matthias: That’s a good example. In batch processing, knowing the composition of the raw material is crucial. That’s why sorting is such an important part of our process, before anything goes into the reactor. Each item is identified and sorted according to its material type. First, we wash, clean, and shred the items. Depending on their properties, we either keep them in the material stream or remove them completely. Materials such as EVOH or nylon can affect the process’s efficiency. These materials behave differently in the reactor and must be separated as much as possible during the mechanical purification step.

So, after sorting, you end up with different streams: clear bottles, colored bottles, and multi-layer packaging. Is there a specific recycling process for each of these streams?

Eric: Yes, and that’s precisely where the challenge lies. The key to a functioning circular economy is managing variability in inputs. Many companies make the mistake of trying to apply linear economic logic to circular systems. But that doesn’t work. The most important thing also is how resilient your process is to variability in the feedstock. If they are not resilient to variability - it will never work. It will remain a beautiful project on the lab table. It will never become an industrial plant.

Matthias: In a linear system, the raw materials - such as EG or PTA for PET - are standardized. You order them and receive consistent quality every time. In a circular economy, however, the feedstock is waste, so it is never consistent. Its composition changes constantly. Success depends on – as Eric mentioned -how well you can manage this variability. Where are your thresholds? How tolerant is your process? What happens when the material’s density or fluidity changes?

So, the process of scaling up is pivotal to success?

Matthias: Yes, many lab-scale projects fail when it comes to scaling up. In the lab, everything works under controlled conditions. However, if your industrial process cannot handle feedstock variability, it won’t succeed. It may look great on paper, but it will never make it past the pilot phase.

During our PETnology conference, Darrell Smith from Western Containers raised a user topic. He reported that they work with rPET from mechanical recycling. The issue is that injection molding works perfectly, but blow molding is difficult. What is your experience with your Renew material in PET injection and blow molding processes?

Eric: One of our process’s key advantages is that the recycled material we produce is indistinguishable from virgin PET in terms of quality, performance, and processability. This allows us to use it directly in production lines as if it were virgin material, without having to adjust settings, tools, or process parameters. This is good news for operators because it maintains manufacturing efficiency and flexibility.

______________

''We can’t build a circular economy on good intentions alone. It has to work within market realities – it must be profitable, scalable, and attractive. Otherwise, it won’t last.'' - Matthias de Vel.

______________

But it’s much more expensive, isn’t it?

Eric: Yes, it is more expensive than mechanical recycling, and more capital-intensive but the benefit and value is much higher. Nevertheless, from an operational perspective, it is a groundbreaking innovation. The plant requires no additional attention, and everything runs smoothly. I would like to reiterate the life cycle costs that we reviewed previously.

Interesting details about bottle production with rPET compared to your Renew material. More generally, PET is also used for films and copolyesters. Does your chemical recycling process require different plant systems or process settings for all these applications?

Matthias: That’s the beauty of it: the system is uniform. We break everything down to the molecular level. From there, it doesn’t matter if the material is used for a bottle, a tray, or a multilayer film. The molecules are the same, so we can rebuild them into any PET or copolyester application, just as we can with virgin, fossilbased, feedstock.

Please provide an example that illustrates how chemical recycling overcomes the limitations of mechanical recycling.

Eric: For instance, today after one or several cycles, the aesthetic degrades and the color becomes light grey. With chemical recycling, because we go back to the building blocks of PET, after each cycle, the recycled PET is virgin-like.

Matthias: The mechanical and aesthetic properties determine how far you can go. There is a market for these types of rPET materials, but there is a real limit to the quality that can be achieved. The problem is cleaning. Mechanical recycling cannot remove all the impurities that affect color, clarity, and performance. That is the technical hurdle. Chemical recycling, on the other hand, resets the material at the molecular level. This allows us to improve both quality and application possibilities.

The real challenge lies not only in the technology but also in the consistency and scope of the inputs. So, we must ask ourselves: Are we there yet? And: at what level can we talk about a true circular economy?

Matthias: That’s a valid question. But the truth is, the volume is there. There are huge amounts of polyester waste, much of which is not recycled Therefore, I do not see the availability of raw materials as a problem.

Eric: We take the issue of infrastructure very seriously. It’s not just a matter of identifying materials, but also of ensuring that systems are in place for collection, transport to our plants, and sorting. This is a major challenge, especially since this infrastructure is still far from universal. We haven’t encountered any significant volumerelated issues in North America and Europe, where we’ve already started operations. The big question is, what’s in it for sorting centers, oversort centers, and MRFs to support this system? Ultimately, the goal is to create added value for everyone involved in the chain.

Greenwashing

A critical question: Chemical recycling is often criticized for being energy-intensive. Some even claim that it’s just greenwashing. How do you respond to that?

Matthias: That’s a valid question, and it’s one that we’ve taken seriously from the beginning. We’re working hard to address these issues headon with facts, data, and clear communication. First, “chemical recycling” is a broad term that encompasses many different technologies. We’ve already discussed that. Our process is materialto-material recycling, which involves no fuel production or incineration. We break down waste materials and rebuild them into high-quality materials. This is a true circular approach. Second, we have always been committed to transparency. Our processes are certified by independent bodies, particularly with regard to mass balance, a topic that is often criticized. As long as it is verified and openly communicated, we consider mass balance a legitimate and necessary tool.

_______________

''We’re working hard to address these issues head-on with facts, data, and clear communication. First, “chemical recycling” is a broad term that encompasses many different technologies.'' - Matthias de Vel

_______________

Future plans, business model, scaling and partners

Please describe your current market situation.

Matthias: Our plant in Kingsport, Tennessee, is designed to produce 100,000 tons of recycled PET per year. While that’s a large operation in absolute terms, in the context of the global PET market - or even just Europe - it’s relatively small.

Eric: To put that into perspective: around 5 million tons of PET are put on the European market every year. Although our plant is large, it can only handle a small portion of the total.

Could you provide an overview of your expansion plans or upcoming investments?

Eric: We currently have one operating plant in Tennessee and announced a second project in the USA. We have also begun developing a greenfield site in France. Our immediate focus is on operating these three plants successfully. There is ample room for growth. If you consider the overall market and apply the necessary proportion of recycled content to the total amount of PET brought to market each year, the potential output is easily ten times higher than that of these three plants combined. It’s only a matter of time before the market adapts to circular economy practices. Then, real scaling will take place.

Do you carry out chemical recycling processes on a laboratory scale here at the site?

Mathias: Yes, but not to simulate the entire process. Our laboratory work focuses on analyzing the raw materials. Since the quality of the raw materials is crucial to our recycling process, we conduct simulations early on to evaluate how different materials will behave in our large-scale plants. This allows us to better predict the behavior of the process and make data-driven decisions before scaling up.

______________

''For this model to be successful, they must commit to using recycled materials, which means adopting something new. It requires a mindset shift at all levels.'' - Eric Dehouck.

______________

Are you planning to enter the Asian market as well?

Eric: Not at the moment. We have plenty to do in EU and USA for the time being.

The source material for your process is diverse, as are the sources themselves. What role do partners play in scaling up?

Matthias: A major one. Scaling our process isn’t something we can do alone. It requires collaboration along the entire value chain from collection and sorting to acceptance by our customers and consumers, which includes collection systems, pre-sorting facilities, MRFs, and collaboration with mechanical recyclers.

Eric: Exactly! It’s important for sorting centers to recognize that even heavily contaminated or multilayered PET has value. This is part of the learning process, demonstrating that sorting and recovery are worthwhile. At the other end of the chain, our customers also play a role. For this model to be successful, they must commit to using recycled materials, which means adopting something new. It requires a mindset shift at all levels.

Do brand owners also play a decisive role as partners in this transformation?

Eric: Absolutely. Brand owners are important partners. They convey this message to consumers not only by complying with regulations but also through their marketing strategies. They play a key role in shaping a better future by ensuring that all currently unrecycled materials are recycled using advanced technologies like ours.

Actually, everything speaks in favor of business models and investments in recycling technologies, whether for mechanical or chemical PET recycling. Currently, however, recycling seems to have stalled. Why is that? Is now a critical moment for investments?

Eric: Definitely. This is a critical moment. We are in a very difficult environment, and, in my opinion, the biggest problem at the moment is the lack of a clear regulatory framework. This is the worst thing that can happen, not just for us, but for the circular economy as a whole. In principle, companies are willing to invest in recycling - Eastman included - but the investments are high and long-term. Without regulatory clarity, these investments come to a standstill. Last year, we saw exactly that: the industry delayed projects and postponed decisions because the outcome was too uncertain.

Matthias: That is why we are working closely with the European Commission to create more clarity. We are pushing for mirror clauses, strict quality criteria, and effective anti-fraud mechanisms. These are the pillars that can ensure stability and promote real investment. If these changes do not take place or fail due to a lack of guidelines, we will all lose out.

So, do regulatory frameworks actively promote investment and thus also innovation?

Eric: I think regulations are helpful, especially when it comes to binding targets, such as recycling quotas. They provide direction and a long-term vision, both of which are essential. However, they must also be realistic and protect regional competitiveness. Currently, we are seeing a wave of imported products from regions where recycled materials are not permitted in consumer products, and these products are in direct competition with locally manufactured recyclable materials. That is a real problem.

Matthias: At the same time, we see brand owners making strong sustainability commitments. However, these goals are often put on hold when financial goals take priority. As a result, we are caught between ambition and market pressure.

Eric: That’s why collaboration along the entire value chain is so important, not just in theory, but in practice. We all have a stake in this. If we’re not already working together, we need to start. The whole system comes to a standstill if the brand owner isn’t willing to invest in or use recycled ingredients.

Global plastic agreement

On the other hand: Eastman and other companies are ready to invest in recycling. Why can’t governments agree on a plastics agreement? What are your thoughts on the failure of the UN Plastic Conference in Geneva?

Eric: Today, we see that many EU recyclers are struggling while facing competition from third countries that are not playing with the same rules; the only way to develop a circular economy in Europe is to consider that EU waste first must counts towards the targets define by the EU commission. It is not a question of technology, business or supply chain, it is an ethical question: EU has developed this ecosystem to recycle waste, so let’s make sure we recycle our waste first, otherwise it is a non-sense and EU is becoming the trash can of the world, we will not be competitive to recycle our own waste and all the value chain and know-how will move to third countries.

_______________

''Collaboration along the entire value chain is so important - not just in theory, but in practice. If we’re not already working together, we need to start.'' - Eric Dehouck

______________

My last question is a personal one. What drives you? What is your personal motivation behind all this?

Eric: Throughout my career, I have been involved with issues related to change in the energy and environmental fields. In my opinion, establishing a circular economy in the plastics industry is one of the most important transformations we can undertake. This is important for humanity, the planet, and future generations. When it comes to change, I believe you have two options. You can either stand on the sidelines and comment, saying what’s good and what’s bad and expressing your opinion from afar. Or, you can step into the arena where things are tough and imperfect, but where you can actually make a difference. That’s why I decided to enter the plastics industry and try to be part of the solution. I believe you can have the greatest impact there, both on the economy and on society. That’s not just my motivation, though. I see it in all of our teams, including engineering, sales, communications, and management. We all share a common goal. We’re all on board because we believe it’s worth it. That’s why we invest so much - not just money, but genuine commitment.

It’s been a pleasure talking with you – thanks for sharing your perspective on plastics recycling.

The comPETence center provides your organisation with a dynamic, cost effective way to promote your products and services.

magazine

Find our premium articles, interviews, reports and more

in 3 issues in 2025.