One result was that the researchers were able to confirm their earlier thesis that it really does rain diamonds inside the ice giants at the periphery of our solar system. And another was that this method could establish a new way of producing nanodiamonds, which are needed, for example, for highly-sensitive quantum sensors. The group has presented its findings in the journal Science Advances (DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abo0617).

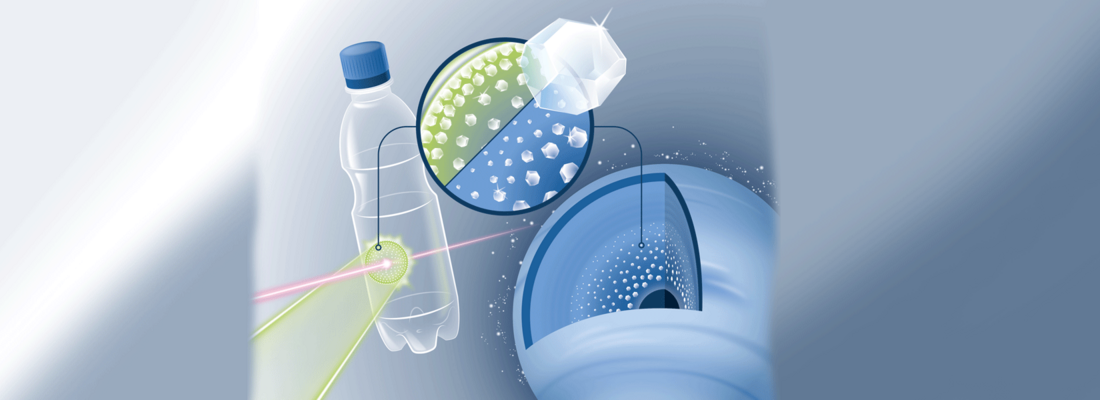

The conditions in the interior of icy giant planets like Neptune and Uranus are extreme: temperatures reach several thousand degrees Celsius, and the pressure is millions of times greater than in the Earth’s atmosphere. Nonetheless, states like this can be simulated briefly in the lab: powerful laser flashes hit a film-like material sample, heat it up to 6,000 degrees Celsius for the blink of an eye and generate a shock wave that compresses the material for a few nanoseconds to a million times the atmospheric pressure. “Up to now, we used hydrocarbon films for these kinds of experiment,” explains Dominik Kraus, physicist at HZDR and professor at the University of Rostock. “And we discovered that this extreme pressure produced tiny diamonds, known as nanodiamonds.”

Using these films, however, it was only partially possible to simulate the interior of planets – because ice giants not only contain carbon and hydrogen but also vast amounts of oxygen. When searching for suitable film material, the group hit on an everyday substance: PET, the resin out of which ordinary plastic bottles are made. “PET has a good balance between carbon, hydrogen and oxygen to simulate the activity in ice planets,” Kraus explains. The team conducted its experiments at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California, the location of the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), a powerful, accelerator-based X-ray laser. They used it to analyze what happens when intensive laser flashes hit a PET film, employing two measurement methods at the same time: X-ray diffraction to determine whether nanodiamonds were produced and so-called small-angle scattering to see how quickly and how large the diamonds grew.

A big helper: oxygen

“The effect of the oxygen was to accelerate the splitting of the carbon and hydrogen and thus encourage the formation of nanodiamonds,” says Dominik Kraus, reporting on the results. “It meant the carbon atoms could combine more easily and form diamonds.” This further supports the assumption that it literally rains diamonds inside the ice giants. The findings are probably not just relevant to Uranus and Neptune but to innumerable other planets in our galaxy as well. While such ice giants used to be thought of as rarities, it now seems clear that they are probably the most common form of planet outside the solar system.

The team also encountered hints of another kind: In combination with the diamonds, water should be produced – but in an unusual variant. “So-called superionic water may have formed,” Kraus opines. “The oxygen atoms form a crystal lattice in which the hydrogen nuclei move around freely.” Because the nuclei are electrically charged, superionic water can conduct electric current and thus help to create the ice giants’ magnetic field. In their experiments, however, the research group was not yet able to unequivocally prove the existence of superionic water in the mixture with diamonds. This is planned to happen in close collaboration with the University of Rostock at the European XFEL in Hamburg, the world’s most powerful X-ray laser. There, HZDR heads the international user consortium HIBEF which offers ideal conditions for experiments of this kind.